Overview of What the history of U.S. protests illuminates about today (Code Switch — NPR)

This Code Switch episode connects recent violent confrontations between federal immigration agents and protesters in Minneapolis to a broader history of protest in the United States. Host B.A. Parker speaks with Professor Gloria J. Brown Marshall (author of A Protest History of the United States) about what protests actually do, why they often take years to produce change, the many forms protest can take, the central role of young people, and the recurring pattern of progress followed by backlash.

Key takeaways

- Protests rarely produce instant, TV‑style fixes. Real social change is usually the result of sustained, strategic effort over years or decades.

- Protest takes many forms: street marches, strikes, sit‑ins, boycotts, individual acts (e.g., Rosa Parks), refusing to patronize businesses, symbolic gestures (taking a knee).

- Young people have historically been and continue to be central to protest movements because of time, networks, and willingness to take risks.

- Protest is costly: participants frequently face economic loss, arrest, violence, and sometimes death — but a relatively small fraction of people acting can secure benefits for many.

- Movements provoke organized backlash; for every advance there are counter‑movements seeking to roll gains back. Expect and plan for that.

- Understanding the history and strategy of past protests helps activists set realistic goals and tactics today.

Topics discussed

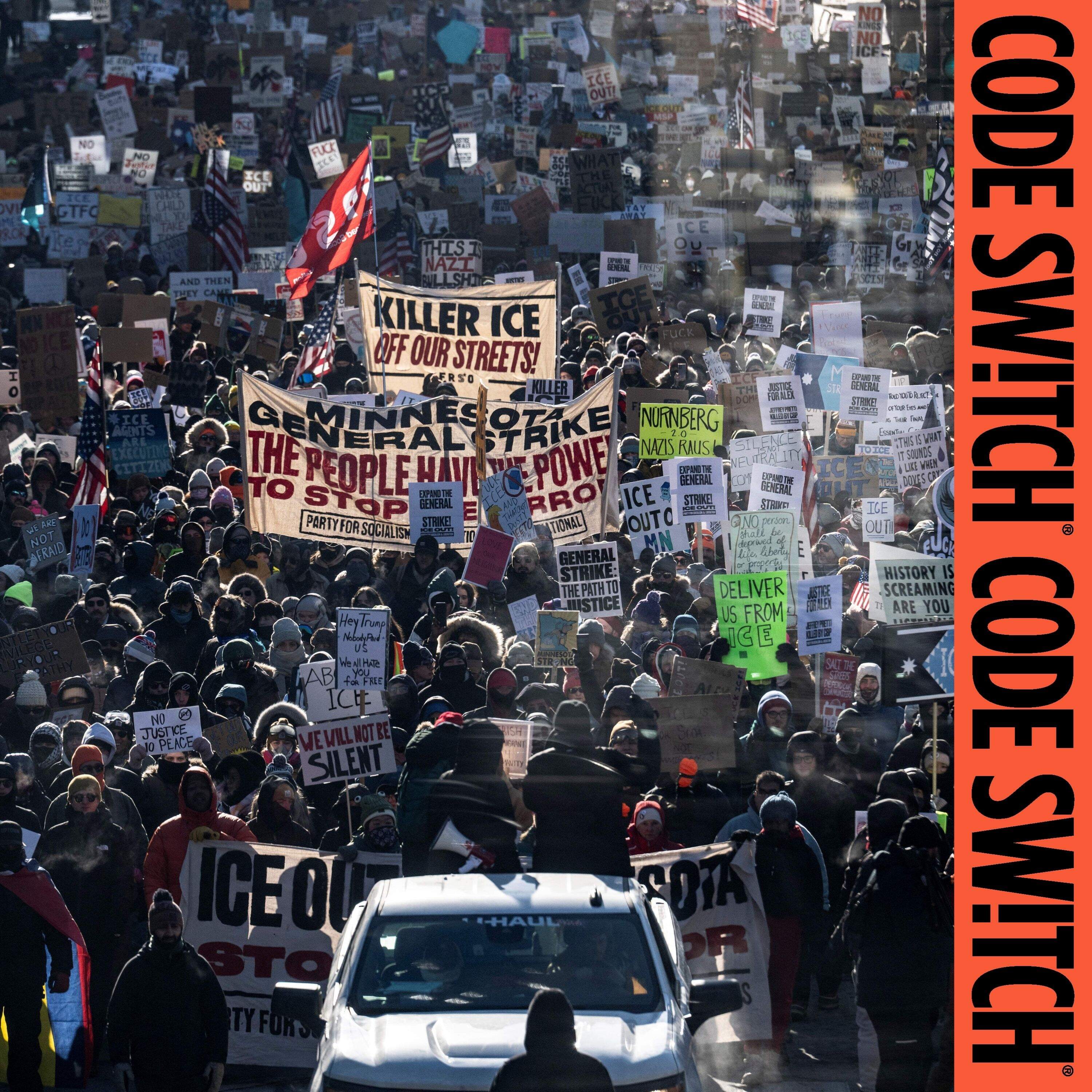

- Recent Minneapolis unrest and the shooting of protesters by federal immigration officers; video evidence contradicting official narratives.

- Why Minneapolis, shaped by the George Floyd protests, is a focal point for organized resistance.

- Gloria J. Brown Marshall’s motives for writing A Protest History of the United States: to recover marginalized protest histories and to inform present activism.

- Historical case studies:

- Labor struggles that achieved the eight‑hour workday through strikes, slowdowns, and organizing (coal miners, company towns, Mother Jones).

- The Montgomery bus boycott and broader Civil Rights Movement’s prolonged organizing that led to 1960s legislation.

- The Tinker v. Des Moines example of student protest (armbands) and many anti‑Vietnam War campus movements.

- Sanitation/trash strikes and the disruptive power of essential‑service strikes.

- Practical insights about protest strategy, intergenerational roles, and civic education.

Notable quotes & insights

- “People think protests should work almost instantly, like in TV…they don’t show that the other side is saying, ‘We’re going to take this ground back.’”

- “Protest is empowering. It allows people to lift that weight off their shoulders and be part of something greater than themselves.”

- “There are ‘freedom freeloaders’ — people who reap the benefits of protest without participating.”

- Rights are often on paper long before they are realized in practice; protests make written rights into lived realities.

- The pattern: two steps forward, one step back — but the steps forward are necessary to avoid perpetual decline.

Historical examples and lessons

- Eight‑hour workday: codified early but required labor organizing, strikes, and national pressure before becoming widespread.

- Coal miners & company towns: organizing involved outside support, unionization, and coordinated strategies under heavy repression.

- Civil Rights: strategic use of student protesters, economic boycotts, and local organizing built toward national legislative change over a decade.

- Anti‑war movement: sustained information campaigns and campus mobilization helped shift national policy and political fortunes.

Practical recommendations for activists, parents, and organizers

- Broaden your concept of protest: teach young people about non‑street tactics (boycotts, refusal, workplace actions, legal cases).

- Prepare for long campaigns: set intermediate goals, anticipate backlash, and build institutional supports (legal aid, strike funds).

- Emphasize strategy and research: know the policy levers, legislative calendar, and economic pressure points related to your cause.

- Encourage intergenerational cooperation: young people often lead direct action, while older allies may provide resources and institutional leverage.

- Recognize the costs: participants should understand potential economic and legal consequences — and communities should prepare mutual support mechanisms.

Why this matters now

- Current clashes in Minneapolis underscore how protest remains a frontline mechanism for holding state power accountable — but also how dangerous and contested it is.

- Studying protest history helps activists and the public set realistic expectations, use a wider toolbox of tactics, and sustain long campaigns that can survive backlash.

Episode credits & further listening

- Guest: Professor Gloria J. Brown Marshall, John Jay College (A Protest History of the United States)

- Host: B.A. Parker; producers and editors credited in the episode.

- Find the episode on NPR Code Switch (podcast platforms or npr.org) and Gloria Marshall’s book for deeper historical detail.