Overview of Episode 3: Better Safe Than Sorry

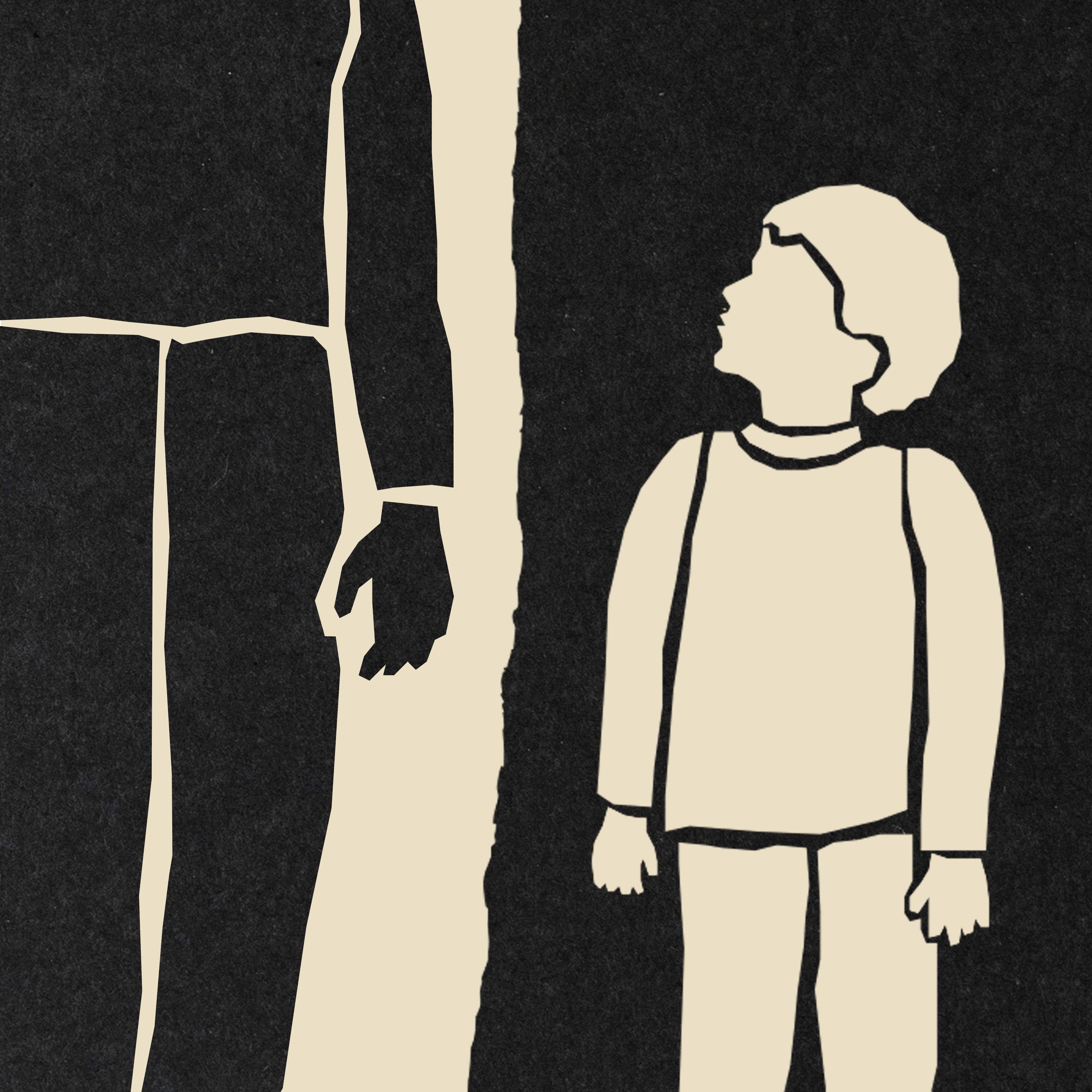

This episode (also titled "The Preventionist") examines how the child-welfare principle "better safe than sorry" can fracture families when medical and investigative certainty is lacking. Through the year‑long reporting on Amanda Saranovsky — a Pennsylvania mother whose newborn was found with brain bleeding and fractures and whose family was then split apart — the episode traces the medical assessments, child‑welfare interventions, legal fallout, and long-term trauma experienced by children and parents when abuse is suspected but not clearly proven.

Key events and chronology (Amanda Saranovsky)

- December 2019: Amanda wakes to find her infant on the floor; toddler was in the bassinet. EMTs take the newborn to Lehigh Valley Hospital for evaluation.

- Hospital findings: brain bleed, fractures, hematomas, injuries to bridging veins. Child-protection doctors (Dr. Rashida Doshi and Dr. Deborah Asernio Jensen) conclude "abusive head trauma — near fatality," attributing injuries to violent shaking with impact.

- Children removed: All five of Amanda’s children are placed outside the home; placements include relatives and multiple foster settings (one child moved ~10+ times).

- Criminal charges: Amanda is charged (multiple felonies and misdemeanors), jailed briefly, refuses an early plea, waits years for resolution. After public controversy, she pleads no contest to reckless endangerment with no sentence, to resolve the criminal case.

- Custody: Her youngest son remained with the foster family under a SPLIC (Subsidized Permanent Legal Custodianship) arrangement; Amanda later files for shared legal custody with gradual visitation and therapy.

- Outcome for professionals/system: A county comptroller report (Mark Pinsley) prompted reviews of cases tied to Dr. Jensen; she was removed as medical director and later retired from LVHN, yet continues to consult and lecture and has been hired as an FBI consultant.

Medical disagreement and the role of child-abuse pediatricians

- Hospital doctors (Doshi, Jensen) were highly confident the injuries required adult-level violent shaking and impact.

- Independent review: The reporter showed anonymized records to three other experts (including two child-abuse pediatricians). None agreed the injuries could only be caused by an adult:

- They saw no classic hallmarks of rotational injury, no severe retinal hemorrhages, no neck injury.

- The child had not lost consciousness, was alert, and did not require life‑saving interventions, which made categorizing the case as a "near fatality" puzzling to them.

- One expert would have treated the event as an accident and not reported abuse.

- Core issue: Different clinicians can look at the same medical evidence and reach divergent conclusions — with massive consequences when child removal and criminal charges follow.

Harm of removal: trauma, instability, and ambiguous loss

- Removing children is the most drastic intervention child-welfare systems use; it can itself cause severe and lasting trauma.

- The episode references a University of Michigan law review paper describing "ambiguous loss" — children grieving a caregiver who is not dead but absent and unsure when/if they will return.

- Amanda’s children experienced:

- Multiple placements, exposure to domestic violence in at least one foster home.

- ER visits for pelvic pain and vaginal irritation (no sexual abuse found, but causing panic for the mother).

- Behavioral and mental-health struggles (especially the youngest daughter, who was moved many times and blames herself).

- Statistical context: An estimated nearly 40% of U.S. children face a child-abuse investigation; for Black children, the estimate is ~53%.

Legal and institutional fallout

- Lehigh County comptroller Mark Pinsley released a report alleging wrongful accusations tied to Dr. Jensen; it spurred protests and media attention.

- The district attorney reviewed cases where Jensen was central; at least one lengthy sentence was later reduced, and multiple families filed lawsuits against Jensen and Lehigh Valley Health Network.

- Administrative changes: Jensen was removed as medical director of the Child Advocacy Center, then retired from LVHN. Despite controversy, she has continued to consult (including for the FBI) and to speak at conferences.

- Policy responses: Three states (Texas, Washington, Georgia) now have laws allowing or requiring second medical opinions in certain child-abuse medical determinations.

Policy implications and recommendations from reporting

- Second opinions: Because CAP (child abuse pediatrician) conclusions can be decisive, families and systems would benefit from formal second‑opinion protocols before removal or prosecution.

- Rebalance removal calculus: Law scholars and some counties advise reserving removal for when a child faces "serious imminent harm," not as a default "better safe than sorry" posture — because removal itself can cause severe harms.

- Prevention and family support: Northampton County shifted toward prevention and supports and reduced foster numbers by about half over four years, showing an alternative emphasis on keeping families intact when possible.

- System-wide humility: Courts, child-welfare agencies, hospitals, and prosecutors should recognize medical uncertainty and the possibility of misdiagnosis as part of decision-making.

Notable quotes and insights

- Phil Armstrong (Lehigh County executive): "We want to always make sure if there is going to be an error, it's going to be to help the children stay safe... I think you have to be overprotective for the children."

- Reporter’s central claim: "When it comes to child‑abuse pediatricians and the power they wield, families deserve a second opinion."

- From Amanda: She says she "grieves" the child not being home and is torn between bringing him home quickly or preserving his stability by reuniting slowly.

Action items / takeaways for stakeholders

- For policymakers:

- Consider laws and policies making second medical opinions routine in disputed child-abuse medical findings.

- Invest in prevention programs and family supports to reduce unnecessary removals.

- For hospitals and clinicians:

- Encourage multidisciplinary review and be transparent about diagnostic uncertainty.

- Document reasoning and consider the downstream legal/custodial consequences of categorical language (e.g., "near fatality").

- For courts and prosecutors:

- Factor medical uncertainty into charging and removal decisions; use restraint when risks are not clear-cut.

- For parents and advocates:

- Know your rights to challenge medical findings and petition for independent reviews; keep records and maintain contact whenever possible.

Closing summary

The episode uses Amanda Saranovsky’s ordeal to show how a "better safe than sorry" approach — especially when anchored to a single, contested clinical opinion — can devastate families. The reporting spotlights the medical disagreements that can occur in child-abuse cases, the severe harms of removal and foster instability, and the policy options (second opinions, prevention-first approaches) that could reduce wrongful separations. The central lesson: because scientific and clinical certainty is often absent, systems should build in checks, transparency, and supports before invoking the most destructive intervention.