Overview of Science Friday — "The Largest US Particle Collider Stops Its Collisions"

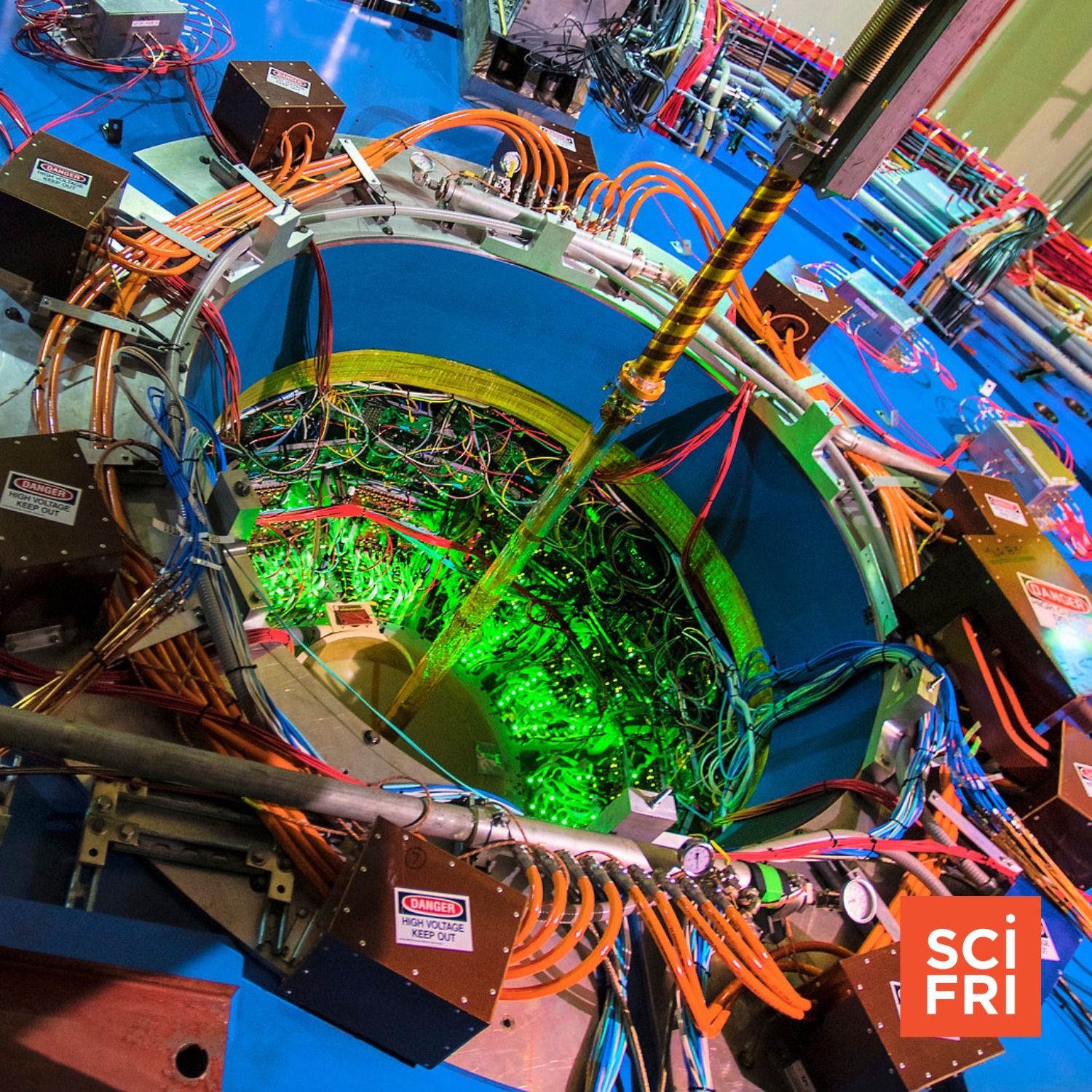

This episode covers the recent shutdown of the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) at Brookhaven National Laboratory, its scientific legacy, and plans for a next-generation collider. Host Flora Lichtman interviews Dr. Gene Van Buren, a nuclear physicist on RHIC’s STAR detector, about what RHIC discovered, why it’s stopping collisions now, and what comes next for U.S. nuclear physics.

Key takeaways

- RHIC (Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider) at Brookhaven, operating since 2000, performed its last collisions; it was the world’s second-most-powerful collider after CERN’s LHC.

- RHIC discovered a quark–gluon plasma (QGP) that behaved not like an expected gas but as a nearly “perfect” liquid with extremely low viscosity—approaching a quantum mechanical limit.

- The shutdown is strategic, not because all questions are answered; the field is shifting focus from hot, dense matter to detailed studies of cold nuclear matter.

- Plans call for building an electron–ion collider (EIC) over roughly a decade by converting one RHIC ring to accelerate electrons and reusing the other ring to accelerate ions.

- Scientists will spend much of the coming years analyzing the large datasets RHIC recently collected; the nuclear physics community is global, so the temporary loss of a U.S. collider affects researchers worldwide.

- Safety concerns (e.g., creating black holes or strange matter) are unfounded—cosmic rays produce similar collisions naturally with no catastrophic effects.

Background & science explained

What RHIC was built to do

- RHIC smashed heavy ions (large, stripped nuclei such as gold) at relativistic speeds to recreate conditions of extremely hot, dense nuclear matter and search for the quark–gluon plasma—an early-universe phase where quarks and gluons are not confined into protons/neutrons.

Quark–gluon plasma (QGP)

- Analogy used: like heating water until molecules separate into steam. Expected to be gaseous, but RHIC found the plasma behaved like a liquid.

- RHIC’s QGP exhibited extremely low shear viscosity—termed a “perfect fluid,” close to the theoretical quantum lower bound on viscosity.

Why heavy ions?

- Heavy (large) nuclei bring many constituents together so bulk properties (liquid vs. gas behavior) emerge; collisions of just a few particles wouldn’t reveal collective states.

Why RHIC is shutting down — and what’s next

- The community decided to shift from creating hotter matter to probing the internal structure of “cold” nuclear matter with higher-resolution probes.

- The next facility is an electron–ion collider (EIC): collide electrons with large nuclei to “shine a light” inside the nucleus and map how quarks and gluons behave when confined.

- Timeline: roughly a decade to convert one RHIC ring into an electron accelerator, build detectors, and commission the new collider.

Short-term plans for researchers

- Analysis phase: upgraded detectors and data-acquisition systems produced large datasets in RHIC’s final runs; researchers expect to spend much of the next several years (possibly two-thirds of the decade) analyzing that data.

- International collaboration: U.S. physicists will continue to work with global facilities and projects; the field is interconnected.

Impact & safety concerns

- Global effect: fewer operating colliders worldwide temporarily disadvantages the entire community, not just U.S. scientists.

- Safety: fears about man-made black holes or catastrophic strange matter are unfounded. High-energy collisions similar to RHIC occur naturally from cosmic rays; no harmful effects have been observed.

Notable quotes

- "It's absolutely a celebration." — Dr. Gene Van Buren on RHIC’s shutdown

- On the plasma: "one of the most ideal, perfect liquids that anyone could ever create."

- "We're all living on a collider right now." — referencing natural high-energy collisions from cosmic rays

Actions & recommendations for listeners

- For follow-ups and deeper understanding: watch for Brookhaven/Nuclear Physics community releases on RHIC data analyses and developments on the EIC.

- If you want to track progress: follow Brookhaven National Laboratory and the STAR collaboration for data papers and timelines for the EIC.

Host/guest details: Host Flora Lichtman; guest Dr. Gene Van Buren, nuclear physicist at Brookhaven National Laboratory (Upton, NY). Produced by Charles Berkquist.