Overview of How Alphafold Has Changed Biology Research, 5 Years On

This Science Friday interview (host Ira Flatow) features John Jumper, a lead scientist at DeepMind and co‑recipient of the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry as described in the episode, reflecting on five years of AlphaFold. They review what protein folding is, how AlphaFold works, where it’s already changed research, its limits, implications for drug discovery, compute/energy considerations, and the next technical steps (AlphaFold 3 and integrating specialist models with language models).

Key takeaways

- AlphaFold transformed structure prediction from slow, costly experiments (often >$100k and many months) to fast computational predictions with confidence estimates, creating reliable hypotheses for experiments.

- The system learned from ~200,000 experimentally solved structures in the Protein Data Bank and uses evolutionary information across species to improve accuracy.

- AlphaFold is most helpful for understanding biology, interpreting mutations, guiding protein design, and accelerating parts of drug discovery — but it is not a shortcut that replaces the full, long drug‑development pipeline.

- Major limitations: intrinsically disordered regions, proteins with few homologs (rapidly evolving proteins, obscure organisms), and sparse data for non‑protein molecules.

- AlphaFold 3 expands capability beyond proteins to model interactions with DNA, RNA, small molecules and ions — improving predictions of binding and complex assemblies.

- Future impact likely comes from combining high‑performance specialist models (like AlphaFold) with large language models that can reason across literature and workflows.

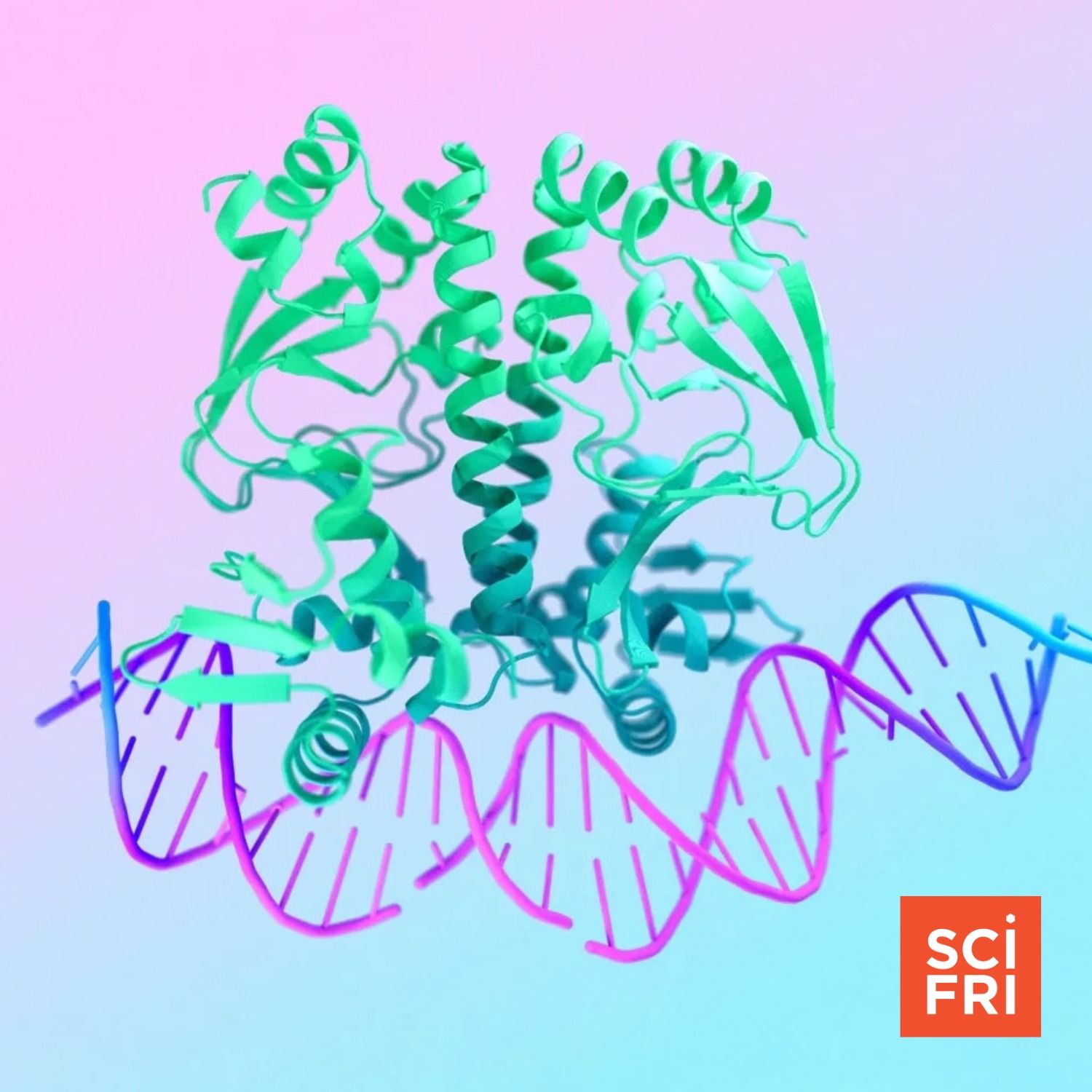

How AlphaFold works (concise)

- Input: amino acid sequence (plus multiple sequence alignments that encode evolutionary relationships).

- Training data: experimentally solved structures from the Protein Data Bank.

- Output: 3D atomic structure predictions plus a confidence metric (so users know when the model is uncertain).

- Performance: numerical metrics (e.g., ~90% on GDT for many targets) are useful but the most practical value is that predictions are actionable, reliable hypotheses for lab follow‑up.

Applications and examples

- Biology research: interpreting how mutations affect structure and function; providing structural context to make sense of experimental data.

- Protein design: guiding engineering of proteins and biological machines.

- Vaccines: used by researchers (example cited: Oxford’s malaria vaccine work) to choose structurally meaningful sequence regions for immunogen design.

- Drug discovery: AlphaFold 2 helped with protein structures; AlphaFold 3 aims to predict protein–small molecule interactions to support lead identification and optimization.

- Evolutionary studies: structure informs evolutionary relationships and functional inference.

Limitations and caveats

- Intrinsically disordered regions: some proteins or regions are biologically floppy and have no fixed structure for AlphaFold to predict.

- Lack of homologous sequence data: proteins with few evolutionary relatives are harder to predict accurately (e.g., some viral proteins or proteins from obscure organisms).

- Data scarcity beyond proteins: far fewer examples of DNA/RNA/small‑molecule complexes reduce predictive power for those classes.

- Drug discovery is a multi‑factor, long timeline: success requires optimizing many properties (solubility, membrane permeability, metabolism, toxicity), so structure prediction alone does not produce drugs overnight. Typical drug timelines remain years; computational advances shorten parts of the process but do not eliminate experimental and clinical testing.

AlphaFold and AI drug discovery

- AlphaFold inspired downstream efforts (including DeepMind spin‑off Isomorphic Labs) but no AI‑designed drug had reached market within five years as of the interview.

- Reasons: drug development requires solving many orthogonal problems beyond binding mode prediction; clinical validation and timelines (often 7+ years) are long.

- Expectation: AlphaFold‑derived tools speed specific parts of discovery (binding prediction, hypothesis generation), reducing effort and improving prioritization, but they are part of a larger tech stack needed to produce drugs.

Compute and environmental considerations

- AlphaFold models (AlphaFold 2: ~128 GPUs; AlphaFold 3: ~256 GPUs; earlier versions used TPUs) are computationally significant but far less energy‑intensive than many experimental approaches (e.g., synchrotron experiments).

- Compared to large language models, AlphaFold uses much less compute — but broader economic and substitution effects should be considered when assessing overall energy use of AI in science.

The future: AlphaFold 3 and AI fusion

- AlphaFold 3 broadens the “structural biology” scope to include DNA, RNA, small molecules and multi‑component assemblies, improving interaction and binding predictions.

- A promising direction is fusing specialist predictive models with large language models to create systems that can reason over sequences, structures, and the scientific literature — enabling better scientific workflows and automated hypothesis generation.

- Jumper expects incremental but meaningful acceleration in structural biology (he estimates a ~5–10% speedup for the field) and continued technological build‑out needed for larger impacts (e.g., drug development).

Notable quotes from the interview

- “Proteins are a couple‑thousand‑atom machines… [they] fold up into a really intricate functional shape.”

- “It’s almost like if you had your…Ikea bookshelf, and as soon as you open the box, the bookshelf just built itself.”

- “Structure is a map that helps you make better hypotheses about proteins.”

- “We made the field of structural biology five or ten percent faster as a whole.”

Practical recommendations / action items

For researchers:

- Use AlphaFold predictions as hypothesis generators — always consult the model’s confidence scores and validate experimentally.

- Combine predicted structures with other biochemical and genetic data to design focused experiments (mutagenesis, binding assays, vaccine antigen design).

For labs and companies:

- Invest in integrating structure prediction into discovery pipelines (but plan for the rest of the drug‑development stack: ADME/Tox, formulation, trials).

- Build datasets and standards for non‑protein complexes to improve predictive power for RNA/DNA/small molecules.

For funders and policymakers:

- Support open infrastructure and curated datasets (like the PDB) that make model training and reproducibility possible.

- Consider compute/energy tradeoffs holistically — compute for AI may replace some experimental energy costs but raises other infrastructure questions.

This summary captures the main points John Jumper made about AlphaFold’s technical approach, immediate scientific uses, limits, and how the next phases of AI in structural biology and drug discovery could evolve.