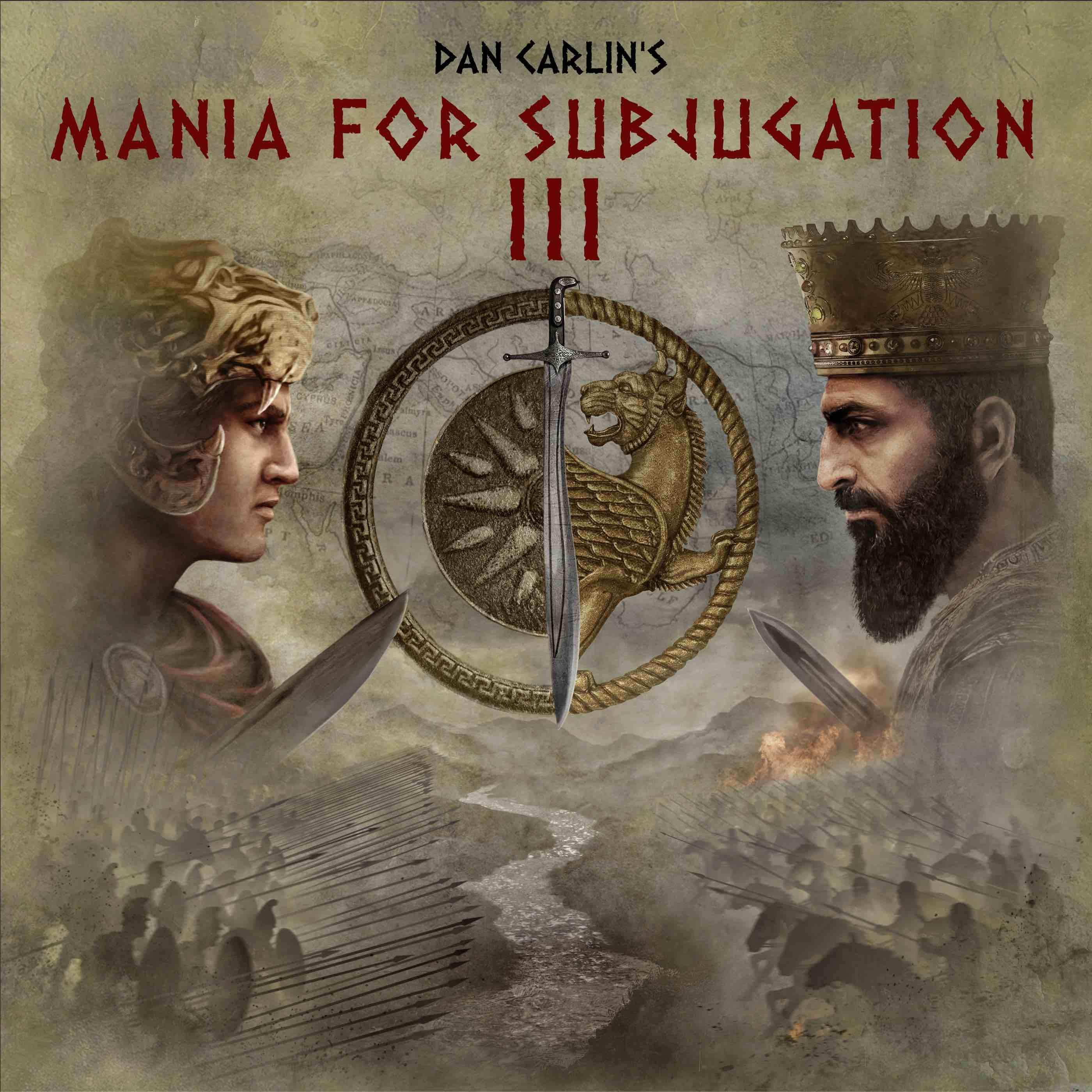

Overview of Show 73 — Mania for Subjugation III

Dan Carlin’s third installment on Alexander the Great covers the crucial transitional winter (335–334 BCE) between the pacification of Greece and the invasion of the Persian Empire. The episode mixes narrative (people, travel, religious rites) with structural analysis (finances, logistics, army composition) and ends with the contested and pivotal Battle of the Granicus. Carlin repeatedly highlights two big interpretive threads: (1) the constraints and momentum of the era (how much anyone on the throne would have been forced down a similar path), and (2) the distinctive personal drives of Alexander — appetite for glory, possible belief in divinity, and a refusal to accept conservative counsel — which push events far beyond what a more cautious ruler might have done.

Key points & main takeaways

- This episode is the “interlude” between subjugating Greece (including Thebes) and invading Persia. A surprising amount of consequential material happens during this apparently quiet winter: a high-level staff meeting, financial crises, personal/familial moves, and religious/propaganda acts.

- Money matters. Alexander inherits heavy debt from Philip II and is running a huge “burn rate” because of a permanent, professional army. Cash shortfalls shape campaign routes, motivate sackings, and explain Alexander’s willingness to sell or pawn royal property and borrow from companions.

- Military momentum vs. individual agency. Many of Alexander’s early gains owed as much to an extraordinarily well-trained Macedonian army and a favorable political balance as to his unique genius — but Alexander’s limitless appetite for conquest (and desire for Homeric glory) makes him push far beyond what most successors would.

- Propaganda and religion are not window-dressing. Alexander consciously uses Homeric imagery, pilgrimages (Troy/Ilium), shrine restoration and claims of divine ancestry to shape loyalties across Greece and Asia — both to win cities and to legitimize his campaign.

- The Persian side is complex and maligned by Greek sources. Modern specialists warn against accepting Greek/late sources’ caricatures of Persia (effeminacy, decadence, chaotic court). Persia’s imperial system, tolerance strategy, and use of mercenaries/cavalry were sophisticated; Greek narratives often simplify or exoticize the enemy.

- The Battle of the Granicus is decisive for momentum but contested in the sources. Arrian and Diodorus give different accounts (timing, method of river crossing, Persian dispositions). What is clear: Alexander personally led the attack, the Persians were routed, regional Persian leadership suffered heavy losses, and several cities and treasuries came over to Alexander, easing his financial problem and accelerating his advance.

Timeline / structure (what the episode covers)

- Return to Macedonia after Thebes’ destruction — last time Alexander sees home and his mother Olympias in person.

- Political housekeeping (elimination of potential rivals in royal family).

- Staff meeting at Macedonia: Parmenio and Antipater (both experienced, elderly generals) advise caution — to marry, secure an heir, and delay. Alexander rejects that counsel and insists on immediate invasion.

- Financial situation: inherited debt, high costs for a standing army, selling/pawning of royal lands, and borrowing from companions. Plutarch anecdote: someone asks “what will you be left with?” — Alexander answers, “my hopes.”

- Persian political context: troubled succession, Bagoas (eunuch/vizier figure in Greek tradition), Darius III’s relatively recent accession, and Persian use of mercenaries and provincial satraps.

- Memnon of Rhodes (Greek commander in Persian service) advises scorched-earth/avoidance strategy — burn supplies, avoid decisive pitched battle, and attack the Macedonian rear/Europe — but local satraps refuse for reasons of honor, local interest, and politics.

- Crossing the Hellespont and ceremonial/propaganda visit to Ilium/Troy (sacrifices, relics, the “Iliad” connection).

- March into Asia Minor and the engagement at the River Granicus (spring 334 BCE): contested accounts but a Macedonian victory with major strategic consequences.

Characters & important figures

- Alexander the Great — 20/21 years old, charismatic, driven by Homeric ideals of excellence (arete) and possibly convinced (or willing to claim) divine ancestry.

- Olympias — Alexander’s mother; in sources she reportedly reiterates claims of divine paternity.

- Parmenio (Parmenion) — senior general of Philip II; trusted, experienced, advocate of conservative strategy.

- Antipater — senior Macedonian statesman/general left in charge of Europe when Alexander departs.

- Memnon of Rhodes — Greek commander in Persian service who counsels scorched-earth tactics.

- Darius III (Codomannus) — the Persian king who faces Alexander; a “new” king in a troubled Persian political climate.

- Bagoas — figure in Greek sources described as a eunuch who allegedly poisoned Persian kings (Greek sources may sensationalize him).

- Hephaestion, Ptolemy, Cletus, others — companions and officers who appear in Granicus accounts.

- Ancient and modern sources invoked: Plutarch, Arrian, Diodorus, Callisthenes (lost but foundational), and modern historians like A.B. Bosworth, Pierre Briant, F.S. Niden, Ian Worthington, Adrian Goldsworthy, Victor Davis Hanson.

Military, logistics and numbers (what Carlin emphasizes)

- Alexander’s invading army (estimates vary): ancient sources place infantry 30,000–43,000 and cavalry ~5,000–5,500; with Parmenio’s vanguard (~8–10k) the total force that can be counted in some reconstructions becomes roughly 45,000–58,000.

- Cost/sustainment: F.S. Niden’s arithmetic estimate cited — monthly payrolls and naval costs produce an annual bill possibly 7,000–10,000 talents; this far outstripped typical city-state expenditures (e.g., 80–100× the sum Athens spent to build the fleet that won in 480 BCE).

- Army composition: Macedonian professional phalanx (long pikes), hypaspists (elite infantry), companion cavalry (shock cavalry), allied Greek troops, light infantry, engineers, camp followers, artists and historians (Callisthenes).

- Persian forces: ancient sources inflate Persian numbers; modern historians argue for smaller, more mobile, and more professional forces than Greek propaganda admits. Persia relied on a mix of royal guard, provincial satrap levies, mercenaries (including Greek hoplites), and large cavalry contingents.

- Mercenaries: Persia used money to buy tactical fixes (hire Greek hoplites, flood markets for mercenaries to deny them to Alexander).

- Tactical debate at Granicus:

- Arrian: Alexander presses an immediate crossing and frontal action; Parmenio’s advice to wait is refused; Alexander personally leads the right wing; a “forlorn hope” assault (pawn sacrifice) draws Persian counter-fire, then successive waves / diagonal advance roll up the Persian line; Alexander killed or routed Persian leaders and was wounded in the fight.

- Diodorus: variant account — crossing occurs at dawn, river plays little role in the fight. Accounts differ on timing, placement of infantry, role of cavalry, and casualty figures.

- Casualties & consequences: ancient casualty claims vary wildly. Many modern estimates stress that Granicus resulted in heavy losses among local Persian satraps and leaders; tens of thousands may have died or been enslaved in subsequent massacres of towns. The immediate effect: capture of treasuries, cities defecting, and dramatic easing of Alexander’s financial pressure and strategic path.

Motives, psychology, propaganda

- Alexander’s drives: personal fame, honor (isêgoros/arete), Homeric-cultural obsession (Achilles as model), appetite for being the best — contrasted often with “realpolitik” motives like finance or balance-of-power.

- Divine claims: tales (from Olympias and later accounts) that Alexander was descended from gods (Achilles/Heracles/Zeus) may have begun in this winter. Whether he truly believed or used it instrumentally is debated — but belief/claims function as a confidence / legitimacy multiplier.

- Propaganda & ritual: pilgrimage to Troy, sacrificial acts, temple restorations and transfer/exchange of “relics” are aimed at uniting Greeks on both sides of the Aegean and legitimizing the expedition as a pan-Hellenic, Homeric enterprise.

- Finance as motive and constraint: Alexander’s borrowing from companions (Plutarch anecdote — when asked what he’d be left with, his reply: “my hopes”) and the campaign’s need for loot shaped routes (target cities with treasure) and decisions.

Battle of the Granicus — contested essentials

- Location: River Granicus (modern Biga in Turkey). Terrain features — steep banks and gravel/stream beds — mattered tactically.

- Two rival ancient narratives (Arrian vs Diodorus) disagree on whether Alexander attacked immediately across the river or waited until dawn to cross; whether the Persians intended to fight, or were deployed more as a show of force; and on how the cavalry/infantry were used.

- Tactical picture (consolidated):

- Initial “pawn” force (forlorn hope) wades in, draws Persian javelin fire and cavalry response.

- Companion cavalry and successive formations cross in diagonal waves, bend the line, and break the Persian cavalry strongpoints.

- Alexander personally fights in the front and is wounded but survives; several Persian satraps and nobles fall.

- Result: Persian regional leadership devastated locally; many cities surrender or shift allegiance; Alexander’s logistical problem (money/supplies) eased due to treasuries falling into his hand.

- Ethical/historical reactions: some historians stress the slaughter of Greek mercenaries (many sources say Alexander massacred rebellious Greek mercenaries attached to Persian forces) and note a grim cost even in a “victory that opens the gates.”

Notable quotes & lines from the episode

- “The old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born. Now is the time of monsters.” — cited (attributed to Gramsci in translation); Carlin uses it as a framing trope.

- Plutarch anecdote: when Alexander pawns/sells royal land, a companion asks “What will you be left with?” Alexander: “My hopes.” (a telling line, repeated by Carlin).

- F.S. Niden on costs: Alexander’s war “might be 7,000 to 10,000 talents a year… 80 or 100 times what Athens spent to build the fleet that defeated the Persians in 480.”

- Will Durant on scope: the invasion “the most daring and romantic enterprise in the history of kings.”

Interpretive tensions & debates stressed by Carlin

- How much of Alexander’s course was forced by structural conditions (army structure, finances, geopolitics) vs. how much was due to his idiosyncratic personality (insatiable appetite for glory, possible claims of divinity)?

- Persian decline myth vs. reality: Greek sources and older historians present a decadent, declining Persia; many modern specialists stress systemic complexity and that Persia was not in inevitable terminal decline.

- Reliability of sources: Arrian, Plutarch, Diodorus and others draw on lost earlier material (Callisthenes, local records). They also interpret battles, speeches, and motives differently; much is contested and colored by propaganda and later literary aims.

- Tactical reconstructions: modern scholars debate the feasibility of frontal river crossings, cavalry deployments, troop densities, and the role of elite units — and the Granicus is a key flashpoint for those methodological arguments.

Practical takeaways / how to use this episode

- If you want a deep, nuanced understanding of Alexander’s early Asian campaign, listen to Parts I–II first (Carlin recommends the whole series).

- Useful secondary sources and scholars mentioned: Arrian (primary narrative source), Plutarch, Diodorus; modern historians Pierre Briant, A.B. Bosworth, Adrian Goldsworthy, Ian Worthington, F.S. Niden, Victor Davis Hanson.

- Use the episode to rethink “great man” narratives: pay attention to structural constraints (logistics, finances, army form) as well as individual ambition and cultural framing (Homeric ideals, religious claims, propaganda).

Quick summary (in one paragraph)

This episode examines the winter interlude before Alexander’s Persian campaign and argues that finances, army structure, propaganda and a fraught Persian polity were as decisive as battlefield genius. Alexander’s bold rejection of conservative counsel, his Homeric self-fashioning (Troy pilgrimage, claims of divine descent), and his willingness to take personal risk coalesce at the Granicus — a battle whose details are contested but whose strategic impact (breakdown of local Persian authority, capture of treasuries and cities) was profound. Carlin uses the moment to probe the balance between structural momentum and personal will in history, while warning against over-simplified Greek-propaganda portraits of Persia.

Further reading/listening suggestions (from episode)

- Ancient narratives: Arrian, Diodorus Siculus, Plutarch.

- Modern works: A.B. Bosworth (Conquest and Empire), Pierre Briant (on Persia), Adrian Goldsworthy, Ian Worthington (By the Spear), F.S. Niden (Soldier, Priest and God).

- Re-listen: Parts I–II of “Mania for Subjugation” for full context on Philip II, Thebes, and the setup for the Asian campaign.