Overview of 985 - The Murder Inc. Doctrine feat. Greg Grandin (Chapo Trap House, 11/10/25)

This episode is a wide‑ranging conversation between Chapo Trap House and historian Greg Grandin on recent U.S. actions in the Caribbean, escalating violence linked by the administration to narcotics interdiction, and the larger historical and ideological framework — from the Monroe Doctrine to the Bolivarian tradition in Venezuela — that shapes U.S.–Latin America policy. Grandin situates current events (fast‑boat killings, military deployments, covert actions, sanctions and corporate interests) within a century‑long pattern of U.S. interventionism, the war on drugs, and competing economic and ideological projects in the hemisphere.

Key takeaways

- The recent U.S. military escalation around Venezuela (including fast‑boat attacks and carrier movements) is best understood as an extension of longstanding U.S. hemispheric interventionism, not a new phenomenon.

- The Trump administration’s approach treats the war on drugs as a literal authorization for extraordinary use of force, and has turned violent interdiction into a spectacle.

- Venezuela is targeted for a mix of ideological and material reasons: oil and energy geopolitics, anti‑Bolivarian ideology (Cuba as the longer‑term prize), and domestic U.S. political posturing (particularly by Florida Republicans).

- The “narco‑state” narrative about Venezuela (e.g., “Cartel of the Suns”) is overblown and often used as manufactured justification for intervention.

- The war on drugs has repeatedly produced the violent outcomes it ostensibly aims to stop; U.S. policies (Plan Colombia, militarized interdiction) have helped create and intensify cartels and instability.

- A full U.S. invasion of Venezuela would be fraught, costly, and unpredictable — unlike prior small interventions (e.g., Panama) it would be logistically and politically much harder to execute and to stabilize afterwards.

Topics covered

- Recent incidents: “go‑fast” boat killings in the Caribbean and Pacific, distribution of attack videos to media.

- U.S. military movements into the Caribbean (aircraft carrier deployments, including discussion of the Gerald R. Ford).

- Alleged covert CIA actions and the public leaking of those activities.

- Chevron, Richard Grenell and U.S. corporate interests in Venezuelan oil.

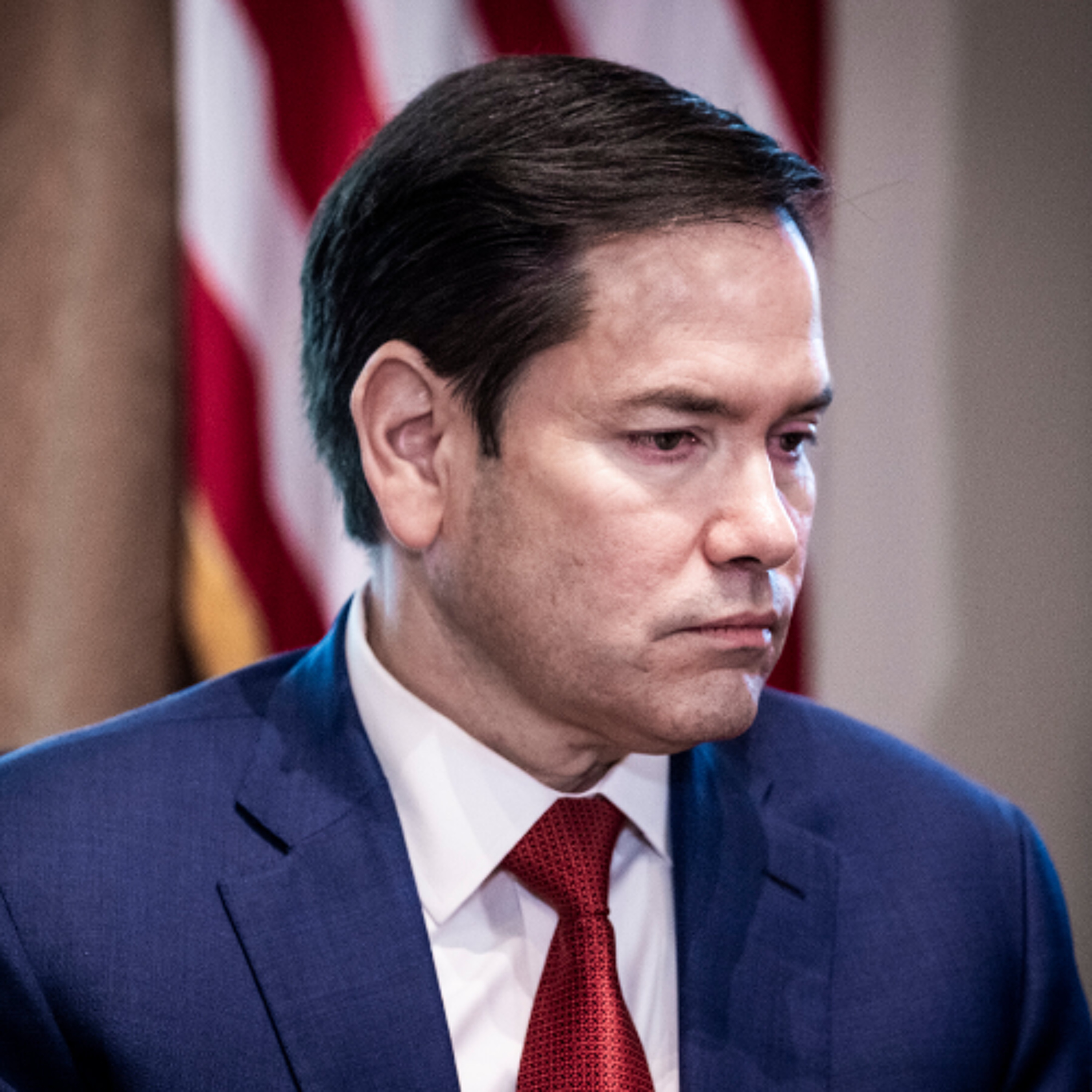

- The political role of Florida Republicans (Marco Rubio) and the ideological push to defeat Venezuela, Nicaragua and Cuba.

- The history and evolution of the Monroe Doctrine and how it is invoked today.

- Bolivarianism, Hugo Chávez’s legacy, Nicolás Maduro’s leadership, and how oil policy shaped Venezuelan politics.

- The history and unintended consequences of the U.S. war on drugs (from Nixon onward, Plan Colombia, DEA militarization).

- U.S. domestic politics: why Democrats and mainstream opposition do not center foreign‑policy threats like invasion in their critique of the administration.

Historical context explained

The Monroe Doctrine (as Grandin frames it)

- Origin: 1823 State of the Union; contains contradictory elements — both anti‑colonial (Europe keep out) and an assertion that events in the Americas affect U.S. interests.

- Evolution: Became a rhetorical and practical justification for U.S. policing of the hemisphere — a “universal police warrant” for intervention and informal empire.

- Modern invocation: Used by nationalist/“America First” factions to justify intervention as hemispheric prerogative and as a domestic‑friendly argument for action.

Bolivar, Chávez and Venezuelan political economy

- Simón Bolívar is a central national symbol in Venezuela; Chávez deployed Bolivarian rhetoric to create a broad populist/leftist coalition.

- Chávez pursued a 1970s‑style developmentalist/redistributional project using oil revenues (reviving aspects of the New International Economic Order).

- Chávez’s approach: mass social programs, alternative institutions, and attempts to use oil wealth internationally. Criticisms included failure to build a cohesive centralized state apparatus (parallel institutions instead of a consolidated state) and insufficient institutional safeguards (e.g., sovereign wealth fund).

- Maduro inherited a weakened political/economic position (low oil prices, sanctions, and internal opposition) and relied heavily on the military for regime survival.

The U.S. war on drugs — origins and consequences

- Grandin traces the militarized drug war back decades: from Nixon-era policies and political uses of drug enforcement to COINTELPRO-like repression and the blending of anti‑drug, anti‑communist and domestic control aims.

- U.S. interdiction and militarized campaigns (e.g., DEA in Mexico, Plan Colombia) often exacerbated violence, fragmented cartels, and increased territorial competition — producing more violent criminal actors, not less control.

- The contemporary rhetoric that equates any corruption or drug bribery with a full “narco‑state” is often a manufactured pretext for intervention.

Recent developments and how Grandin reads them

- Fast‑boat attacks: presented by the administration as anti‑drug operations but characterized by Grandin as premeditated killings used as spectacle; ties drawn between these operations and a “war party” in the administration (Rubio and allies).

- Weaponization of narratives: “Cartel of the Suns” and similar tropes are used to delegitimize Venezuelan sovereignty and justify extreme measures.

- Corporate interests: Chevron’s partial reentry and other oil geopolitics complicate claims that only “oil” motivates U.S. policy — Grandin stresses the mix of ideology and interest.

- Military signaling vs. full invasion: deployment of assets (e.g., Gerald R. Ford carrier) may be more performative than actionable; Grandin doubts a stable, successful occupation is politically or militarily straightforward.

Political implications (domestic and international)

- Domestic politics: Grandin argues mainstream U.S. opposition (liberals/Democrats) tends to keep the political debate domestic, often neglecting forceful foreign‑policy pushes or escalation as central electoral issues.

- International balance: Without control of Brazil and Mexico (large regional powers), the U.S. cannot unilaterally “take” Latin America. Regional politics (Lula/BRICS, other elections) shape the limits of U.S. options.

- Risks of intervention: major social, military and political costs; uncertain outcomes including chaos, insurgency, or quick replacement of leadership by other factions — none of which is easily manageable.

Notable lines and quotes

- Grandin’s coinage: “government by Murder Incorporated” — describing the lethal interdiction spectacle.

- On the Monroe Doctrine: became “a standing universal police warrant for the United States to act at will.”

- On the war on drugs: U.S. policy has repeatedly created the problems it claims to solve (e.g., Plan Colombia increasing coca cultivation).

- On spectacle and policy: Trump turns these operations into public performance — “murder and then passing around the snuff films.”

What to watch / implications going forward

- Continued naval/military maneuvers in the Caribbean and any publicized covert actions — watch how overt vs. covert messaging is used politically.

- Corporate moves (Chevron, Exxon) and legal/sanctions workarounds that tie economic interests to policy decisions.

- Regional electoral outcomes (Brazil, Mexico, Chile, Argentina) that affect the U.S. ability to build hemispheric coalitions.

- Domestic U.S. political response: whether opposition parties or civil society push back on interventionist narratives and the “narco‑state” framing.

- Humanitarian outcomes: continued targeting of small boats/fishermen and collateral harm to civilians if escalation continues.

Bottom line

Greg Grandin places the recent Trump‑era escalation against Venezuela in a long cycle of U.S. hemispheric intervention, driven by a mixture of ideological crusading, economic interest (energy geopolitics), and domestic political spectacle. Grandin warns that the rhetorical and operational choices being made (lethal interdictions, publicized covert actions, invoking the Monroe Doctrine) revive century‑old logics of informal empire and risk repeated, avoidable violence and instability.